PIERRE CHAREAU

4th August 1883 (Bordeaux) – 24th August 1950 (East-Hampton)

BIOGRAPHY

Architect – decorator, creator of furniture and light fittings.

Pierre Paul Constant Chareau was born on 3rd August 1883 in Bordeaux. He was the second of three children of Georges-Adolphe-Benjamin Chareau and Esther Isabelle Carvalho, traders, who had been living in Paris since 1891. Mindful of art in all its forms, the young Pierre Chareau was interested in both painting and music but hesitated between several paths. Eventually, he chose to become an architect and applied unsuccessfully to enter the Académie des Beaux-Arts. He then turned toward the creation of furniture and decided to get to grips with the practice. In 1901, he joined the Parisian offices of the British firm Waring & Gillow, specialists in fine furniture, as a tracer. He developed at this firm and became head designer until his departure in April 1914.

During those years, he met his wife, Louise Dorothee Dyte (1880-1967), nicknamed Dollie, a teacher of English from Britain, whom he married in 1904. Through the contacts that she developed with her pupils, a group of friends formed around Mr and Mrs Chareau which, little by little in the climate of confidence that was establishing itself, would become his original circle of private patrons, the foremost of whom included the Bernheim family: Émile Bernheim and his daughter Madeleine, Raymond Bernheim, Paul and his wife Hélène, Edmond and his daughter Annie.

In parallel, Pierre Chareau worked in the evenings for himself. He studied decoration and architecture and, from 1907, started to present interior perspectives in the style of the English renaissance, in the architecture category of the Trade show of the Société des Artistes Français. In 1908, he carried out alterations to the apartment of Madeleine Bernheim. One of Dollie’s students, she had just married the dramatist, Edmond Fleg. In 1920, for the transformation of the apartment into a duplex, Chareau would take on the entirety of this alteration.

The arrival of the First World War forced Pierre Chareau to stop his business. He was enlisted into the artillery in 1914 and it was only in 1919, at the age of 35, that he opened his own workshop for creating furniture at 54, rue Nollet, in Paris. Dollie became his assistant.

Edmond Bernheim asked Chareau to work on the family’s secondary residence in Villeflix (Noisy-le-Grand). His collaboration with Jean Lurçat, a friend of Jean Dalsace, began: to cover certain items of furniture that Chareau had designed, Lurçat created tapestry cartoons which were produced by his wife Marthe Hennebert in tent-stitch.

One of his first undertakings was the apartment of Annie Bernheim; a student of Dollie’s since 1905, she had just married Doctor Jean Dalsace. At this apartment, located at 195, boulevard Saint Germain in Paris, Pierre Chareau carried out the fitting of the doctor’s surgery, the entranceway and bedroom.

Pierre Chareau wove strong bonds of friendship with some of his clients: at the birth of the first child of the Dalsaces, Chareau created the child’s bedroom, as he would later do at the home of Hélène Bernheim, for whom he created a nursery.

Nevertheless, Chareau’s clientele was not limited to relatives of the Bernheim family, and he was entrusted with designing the interiors of several homes, including those of the photographer Thérèse Bonney (1928), Lise Deharme, Roger Gompel, Octave Homberg, Marcel and Henry Kapferer, Mrs Reifenberg (1927), Mr Simon, etc.

In 1924, he opened a shop, La Boutique, located at 3, rue du Cherche-Midi in Paris and managed by Dollie. In a similar way to an art gallery, this shop allowed him to better introduce his creations and those of his friends to a wider audience. Eager to experiment with new fields of expression, he took part in set production for the avant-garde films of the director Marcel L’Herbier. He collaborated with Robert Mallet-Stevens and Fernand Léger on the films L’Inhumaine (1925), LeVertige (1926) and L’Argent (1928).

Jeanne Bucher, whom Jean Lurçat had introduced to the Bernheims and Chareau, became friends with Dollie and organised art exhibitions at La Boutique until the opening of her own gallery at 5 rue du Cherche Midi in 1929. During the Second World War, she would watch over the workshops and houses that other artists, such as Pierre Chareau, Jacques Lipchitz, Maria Elena Vieira Da Silva and Arpad Szenes had to leave behind, setting up her young artists in their premises: Nicolas de Staël at Chareau’s place, Louis Déchelette at Lipchitz, and Henri Goetz and Christine Boumeester at Vieira da Silva.

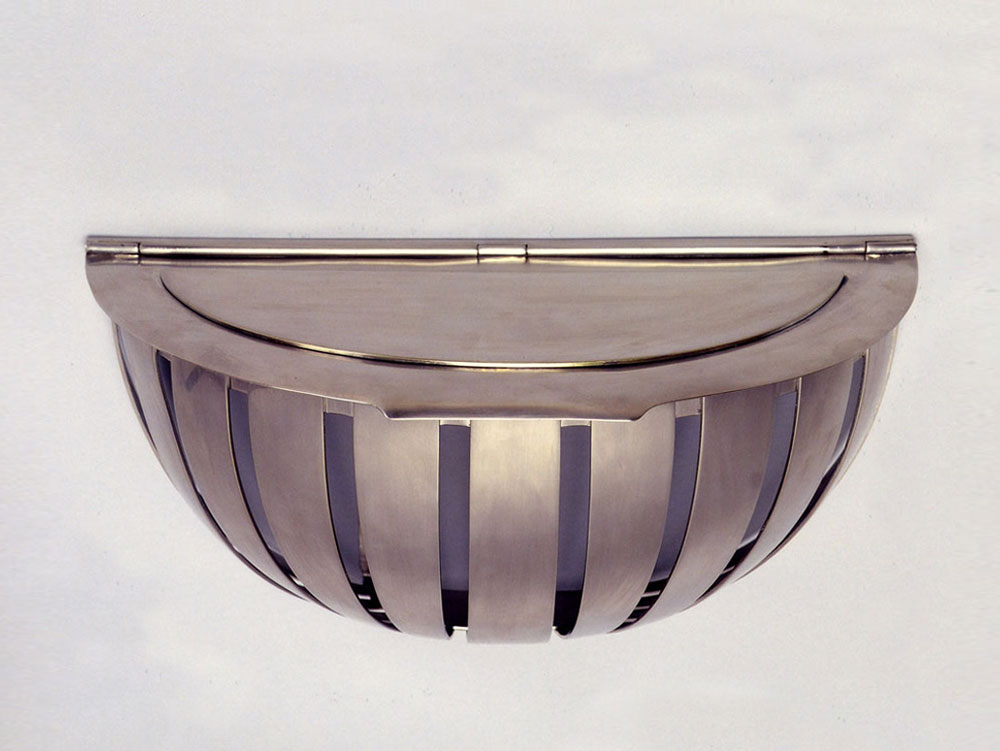

The organisation of 1925’s International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris gave Chareau the opportunity to take part in a collective project alongside the champions of modernity. He was entrusted with a substantial part of the French Embassy’s production presented by the Pavilion of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs, in which he designed a stunning office/library and a lounge. There he produced one of the most striking examples of his work on flexibility and submitted a circular office/library beneath a dome. In this way, light shone into the room but could also be blocked out by a moving ceiling in palm wood which could disappear entirely following the principles of a fan. That same year he created the “Salon de Coromandel” for Hélène Bernheim, the wife of Paul Bernheim, Annie’s cousin.

Aware of the quality of Pierre Chareau’s creations, the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens proposed to collaborate with him on the production of décor and furniture for the villa that he was building for Viscount Charles de Noailles in Hyères, one of the most avant-garde creations of the era.

Pierre Chareau received his first order as an architect in 1925, when Émile Bernheim asked him to design the Club-House of le Golf Hôtel at Beauvallon in the Var. This started his collaboration with the Dutch architect Bernard Bijvoet. In 1927, on behalf of Edmond Bernheim, he started the project of building the Villa Vent d’Aval on the same estate.

At the same time, Paul Bernheim, a cousin of Annie Dalsace, entrusted him with the refurbishment of all the reception rooms of the Grand Hôtel in Tours. For Pierre Chareau this was a new departure, both in the scale of the premises to refurbish and for the number of furniture items to deliver. It was also one of the very first hotel work sites entrusted to a modern architect. In rue Mallet-Stevens he carried out the refurbishment of the apartment of Mr and Mrs Reifenberg.

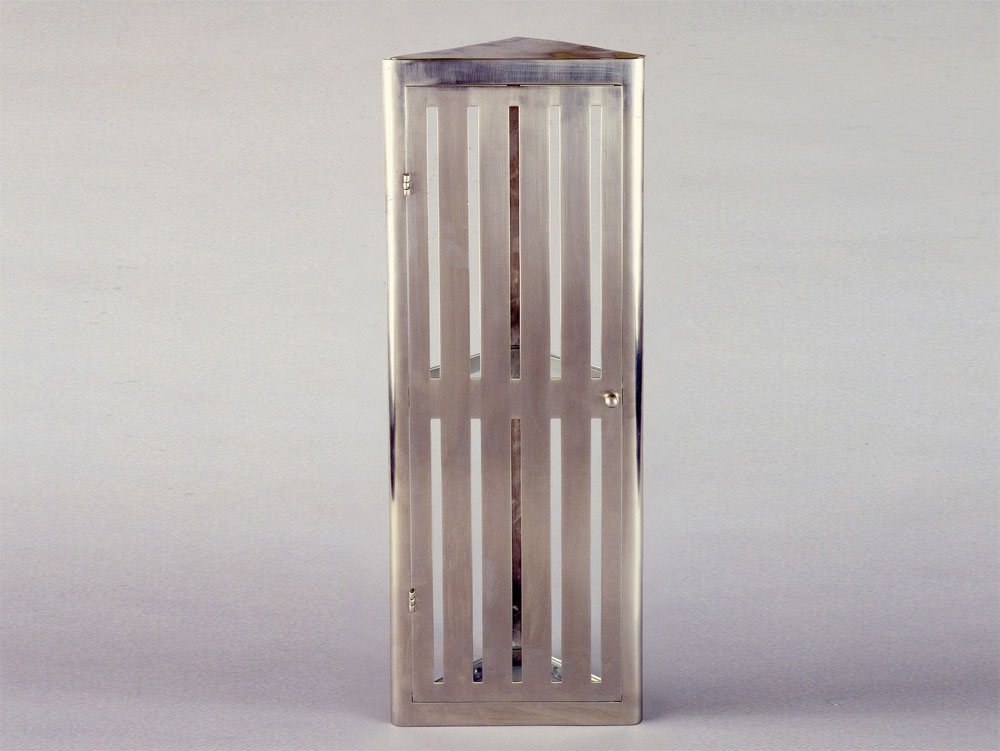

In 1927, Doctor Jean Dalsace, ordered the Maison de Verre (Glass house) project, at 31, rue Saint Guillaume in Paris (1928-1932), which would be his masterpiece. He worked on this project in collaboration with Bernard Bijvoet and the master metalworker Louis Dalbet whom he’d met at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs trade fair of 1922. This creation was a tour de force in which Pierre Chareau managed to build three radiant floors, in the ground floor and first floor of a small obscure hotel, limited by the presence of an old lady who did not want to leave her second-floor apartment.

At the Salon d’Automne of 1929, as a guest of the freshly founded Union of Modern Artists, he presented, furniture designed for the La Semaine à Paris journal, at 28 rue d’Assas. In 1930, he took part with the “dissidents” from the Salon des Arts Décoratifs at the first exhibition of the UAM, at the Pavillon de Marsan. He became an active member of the movement in 1931.

In 1930-1932, Daniel Dreyfus, for whom Chareau had refurbished a studio in 1923-1924, again entrusted the architect with the decoration and internal organisation of a large apartment, located at 9 rue Le-Tasse in Paris. He did the apartment Mr and Mrs Maurice Fahri, at 2 bis avenue Raphaël.

Between 1931 and 1938, Chareau continued his research into furniture flexibility; from 1931 to 1932, he produced desks in glass and copper slabs, for the Lignes Télégraphiques et Téléphoniques company, at 89, rue de la Faisanderie à Paris.

In 1937, the dancer Marie Le Blond, better known by the name Djémil Anik, who was part of the circle of friends of la rue Nollet, commissioned from him the building of a country house on a property located in Bazainville. This time, he had to resolve numerous problems posed by the water supply, the lighting and the heating. Chareau found a solution to these difficulties by using folding walls to let the hot air circulate and allow a transformation of the living room. This idea served to solidify the concept of the house as artwork, which he would develop further in New York.

That same year, as a member of the organising committee of the International Exhibition, he arranged the reception area of the UAM Pavilion, entrusted to Georges-Henri Pingusson, Frantz-Philippe Jourdain and André Louis.

From 1938 Pierre Chareau was given several public commissions. He completed an office for Mr Marx, plenipotentiary minister at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and took part, alongside Francis Jourdain and Louis Sognot, in the fitting out of the offices of the Collège de France. The same year, returning to a material that he used at the start of his career, he produced a cosy-corner in wicker for the apartment of Mrs Marcelle Minet. His last project in France, during the war, was the Foyer du Soldat Colonial at the Grand Palais, for which he designed a set of utilitarian furniture.

In September 1939, France entered the war, and Pierre Chareau tried in vain to leave for London. He left France in 1940, passed through Casablanca in Morocco, where he obtained the papers necessary for travelling on to New York, accompanied by Ève Daniel, the daughter of Jeanne Bucher. He moved into the apartment of André and Sybille Cournand and became a member of the France Forever association in 1941. The goal of France Forever was to show, by means of art and culture, another image of the country and to defend the idea that France remained a democracy. It was a case of swaying American public opinion in favour of a military intervention by the United States in Europe. In this context in 1942 he organised with Dollie, who had just arrived, the Fighting France exhibition at Freedom House. This was followed by diverse outfitting projects including that of La Marseillaise, the canteen of la France Libre.

In 1946, he was appointed as artistic advisor to the French Embassy in New York by the then cultural advisor, Claude Lévi-Strauss. There he organised exhibitions and conferences.

It was in 1947 that he reconnected with architecture when the painter Robert Motherwell commissioned a house in East Hampton from him, that he wished to be produced from sheet metal coming from army surplus. The difficulty of this construction resided this time in the paucity of elements at his disposal; large windowpanes coming from an old greenhouse and metal sheets from the army. Nonetheless, he completed two storeys including several bedrooms and washrooms.

In 1950, his last achievement was also his last attempt to reconnect with a professional practice during his American exile: the refurbishment of “La Colline” for Germaine Monteux and Nancy Laughlin, one a pianist, the other a writer. This project presented difficulties of another kind since it consisted of removing part an existing interior with reduced dimensions. The result seemed to suit its patrons so perfectly that they decided to leave their main residence to live exclusively in the one designed by Pierre Chareau.

That year, according to a letter from Francis Jourdain to George Besson, Pierre Chareau attempted to return to France to end his exile.

He died without doing so, on 21st August 1950 in New-York and was buried at the Saint-Philomena cemetery in East Hampton.